How To Blog About Industry When You're Changing Careers

AHA Scientific Session 2021: Updates in Stroke: Careers & Future Directions in Vascular Neurology

Panelists: Drs. Anjail Sharrief, Ashutosh Jadhav, Louise McCullough, Alicia Zha. Moderator: Dr. Lauren Fournier

The session kickstarted by highlighting the duration of neurology training and the timeline to consider a career path and why is it important to do a fellowship? In current times, there is rapid growth in the field of medicine, with this, there is an increase demand to have specialists and hence choosing a fellowship is important. This session discussed extensively about a career in Vascular Neurology, comprising of panelists with different yet similar background in the field of vascular neurology. There was a shocking revelation in the dearth of vascular neurologists as compared to our counterparts, cardiologists. The graduate ratio of stroke neurologist to that of cardiologist is ~1:10, however, the disease burden is not proportionate. A part of this could be attributed to the amount of exposure we get in acute stroke management during our training and hence can be inclined towards either an inpatient or outpatient setting without a formal fellowship, but wait… there is more to it; The panelists gave us an insight into post stroke care and management, which is also equally important and we don't follow in the post discharge period. And that's when fellowship becomes important as it gives your patient a continuity of care at a community level.

There is more to it than just the title of a vascular neurologist; There are various aspects of stroke care that we can dive into such as health equity in stroke patients, stroke in young, stroke in women to name a few. The newly evolving field of telemedicine/ tele stroke has become an important aspect of our day-to-day practices and is rapidly changing how patient care can be delivered in an effective and efficient manner. When does this become important, as Dr. Jadhav gave an instance, flying a patient from 45 minutes away and treating them acutely doesn't end there, as a stroke neurologist, you have an added advantage of following this patient when discharged to the community especially if there is lack of a stroke neurologist with the gift of tele-medicine and training to ensure secondary care. Drs. Sahrrief and Zhao spoke about the importance of training and practicing telemedicine to stay continually in touch with the patients and communities for their betterment and managing secondary stroke prevention by providing close follow-ups, assessing with social work needs etc. As this form of medicine is becoming more popular and is now being incorporated into ACGME curriculum, it is important to look if the fellowship program can ensure proper training as this can teach us early on to triage patients and manage their care.

Neurointerventional radiology has been steadily gaining momentum in recent times as more trainees from a neurology background are interested in pursuing a career in this field. A summary of the field of neurointerventional radiology including the different training pathways and what is the formula for a successful match was made by Dr. Jadhav. Having addressed this, the panelists stressed the importance of picking a specialty that you are passionate about as this will eventually make the journey worth it.

A topic that most of us want to know and be a part of, RESEARCH. Research in one form or the other is part of our training, the question is, how do we make the most out of this and keep it consistent? Having a research foundation early on in training is important, but what brings this foundation together? The right mentor and environment are of utmost important when you are a novice. As trainees, we can start by familiarizing with clinical research methods, clinical trials, interpreting articles and carry these lessons to further build on in fellowship programs. There are multiple online resources which can help us achieve this, one such example is through AHA which offer courses on epidemiology.

Dr. McCullough discussed, Mobile Stroke Unit, and how it is changing the phase of acute stroke management in the pre-hospital setting and studies are currently looking into cost effectiveness. Stay tuned as more updates will be presented at International Stroke Conference!!!

The panelists then discussed, the "happening lytic", TNK, and its future in acute stroke therapy.

The closing discussion was a question which we have all had at some point in our career, what are the ways to ensure a smooth transition after training; Some important take away points included, if looking for an academic opportunity, how is your support system and resources. In general, it is to understand your worth, negotiating time and money, protected time for your academic interests. The first 3-5 years in any setting is very crucial in establishing yourself and knowing how you want to shape your career. Nobody is a 100% certain, you need to have an open mind and work with the flow. It's good to keep in mind that there is no perfect job and the trick is to learn to evolve and carve the niche for ourselves.

"The views, opinions and positions expressed within this blog are those of the author(s) alone and do not represent those of the American Heart Association. The accuracy, completeness and validity of any statements made within this article are not guaranteed. We accept no liability for any errors, omissions or representations. The copyright of this content belongs to the author and any liability with regards to infringement of intellectual property rights remains with them. The Early Career Voice blog is not intended to provide medical advice or treatment. Only your healthcare provider can provide that. The American Heart Association recommends that you consult your healthcare provider regarding your personal health matters. If you think you are having a heart attack, stroke or another emergency, please call 911 immediately."

Social Media Advice for Early and Mid-Career Professionals from #AHA21

Jessica Monterrosa Mena

The schedule of events as a first-time attendee to AHA Scientific Sessions can be overwhelming! As an early career blogger, I decided to attend sessions to get advice from professionals on managing social media presence in "Social Media in Cardiology- Managing Misinformation as Fellows in Training". It was reassuring to take part in a lively discussion with many participants asking questions ranging from, "How do I start developing my social media presence" to "How do I deal with mansplaining?" We were lucky enough to have experienced panelist give their insights.

There are many benefits to taking part in social media as an early career professional. It can be used as a platform to find role models and mentorship or start project and publication collaborations. These connections can be established by simply joining broad dialogues, tagging experts in a conversation, or sending a direct message to interesting people. Establishing a social media persona can also include creating a place to ask questions, sharing expert consensus, and guiding dialogue in a specific discipline. As field experts and early career scientists, we are uniquely positioned to gather cutting edge information and share our knowledge with broader audiences. In order to be successful in these endeavors, choose your social media platform carefully. Understanding the age-group audience predominating that specific platform can inform the type of content you decide to post and will influence how you frame your ideas.

While participating in an environment that is not curated can allow you the freedom of sharing pictures of your dogs along with scientific news, panel experts also reminded us that everything on social media lives forever. The downsides of social media include hostility, mansplaining, and being discredited and turned into a meme. Not everything you post can be edited, and typos can be an annoyance for yourself and others when conversations are picking up speed. However, when your post turns out to be factually wrong or misguided, a public apology might ensue. Being transparent about how you gathered information and why you are sharing it with others can help establish and maintain trust in quickly developing online discussions.

Things can also get tricky when dealing with misinformation or with patients asking for medical advice. Many patients seek to educate themselves by seeking information online, and practitioners have a responsibility to educate and be effective leaders in this online space. In fact, social media training is becoming a desirable and valuable skills set for many early and mid-career professionals. Professionals can use social media to spread scientific evidence for the greater good but will also need to develop an approach for responding to misinformation. When engaging in difficult conversations, be explicit about the limits of what you are offering and avoid driving more traffic to misinformation pages. Be cautious when engaging with misinformation posts; give others the benefit of the doubt but stay concise in your responses and only provide the correct information. If you are unable to engage in a meaningful discourse you can move on, or if you are so inclined you can call out, block, ignore, or mute hostile people. There is a balance between the benefits you gain from social media and the time you spend online. Overall, to make social media a positive part of your career, make sure to set boundaries, build trust, and be accurate about what you post. Social media can be an effective way to build your professional persona, make meaningful connections, and communicate science if you develop the right approach.

This program is part of the FIT Program at #AHA21. The panelists Danielle Belardo MD, Amir Goyal MD MAS, Martha Gulati MD MS FAHA, Virginia Bartlett, and was moderated by Christina Rodrigues Ruiz, MS and Sasha Prisco MD, PhD.

"The views, opinions and positions expressed within this blog are those of the author(s) alone and do not represent those of the American Heart Association. The accuracy, completeness and validity of any statements made within this article are not guaranteed. We accept no liability for any errors, omissions or representations. The copyright of this content belongs to the author and any liability with regards to infringement of intellectual property rights remains with them. The Early Career Voice blog is not intended to provide medical advice or treatment. Only your healthcare provider can provide that. The American Heart Association recommends that you consult your healthcare provider regarding your personal health matters. If you think you are having a heart attack, stroke or another emergency, please call 911 immediately."

The pursuit of Ideal cardiovascular health: It's never too LATE! But the earlier, the better!

Reza Mohebi, MD

"Cardiovascular health after 10 years: What have we learned and what is the future" was my topic of choice from this year's AHA21 main scientific sessions. It has been over 10 years since American heart Association (AHA) published a formal definition of cardiovascular health (CVH). In the last 10 years, more than 2,000 publications have tried to address the concept of CVH. AHA 2020 impact goal was to improve the CVH of ALL Americans by 20%, while reducing deaths from cardiovascular (CV) disease and stroke by 20%. Seven key health metrics were used to define CVH including: smoking status, physical activity, healthy diet, blood glucose level, blood cholesterol level, and blood pressure. Each metric was stratified into three statuses: poor, intermediate, and ideal. The initial approach was to improve individuals' health from poor status into intermediate status and subsequently to ideal status and later promote and preserve ideal CVH through individual's life(1).

In the last 10 years, many community-based cohort studies including Atherosclerosis Risk in Communities (ARIC), Multi-Ethnic Study of Atherosclerosis (MESA), Women's Health Initiative (WHI), Coronary Artery Risk Development in Young Adults Study (CARDIA), and Cardiovascular Health Study (CHS) have investigated the association of CVH metric with CV outcomes. A meta-analysis of 13 studies showed that as the number of Ideal CVH metrics decrease the relative risk of all-cause mortality and CV mortality increase in a linear fashion(2). Moreover, studies have expanded the impact of CVH metrics on other chronic disease like cancer, chronic kidney disease, dementia, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, and hip fracture(3).

Disappointingly, national data have shown that high CVH is uncommon. Only 7% of U.S. adult population meets the criteria for high CVH, 34% for moderate CHV and 59% for Low CVH group(4). It is estimated that 70% of CV events are attributable to low/moderate CVH and up to 2 million CV events can be prevented if all U.S. adults attained high CVH(5). This implies that potential impact of maintaining high CVH is substantial. The question is how early we should intervene to maintain high CVH.

Prevalence of ideal CVH decline significantly with age. In a study of pooled data from 5 community-based cohort, CVH trajectories were defined starting from age 8 to age 55. 5 unique trajectories have been identified. The prevalence was 30.7% for high rapid decline, 10.3% for intermediate rapid decline, 24.3% for high slow decline, 17.4% for intermediate stable and 17.3% for high stable trajectory(6). These trajectories showed that by age 8, already 20% of 8-year-old children do not have ideal CVH. Loss of ideal CVH metrics occurs at different rate across life span, but late adolescence seems to be a critical time where rapid CVH decline occurs. Moreover, analysis of baseline demographic characteristics by CVH trajectory showed that high stable trajectory is most common among white females and high rapid decline trajectory is most common among African American males. Finally, individuals with high stable trajectory were more likely to have ideal diet and physical activity compared to other CVH metrics at baseline (smoking, blood pressure, glucose, lipid level) suggesting that the best approach to maintain ideal CVH is through promoting healthy behavior.

References:

- Lloyd-Jones DM, Hong Y, Labarthe D, Mozaffarian D, Appel LJ, Van Horn L, et al. Defining and setting national goals for cardiovascular health promotion and disease reduction: the American Heart Association's strategic Impact Goal through 2020 and beyond. Circulation. 2010;121(4):586-613.

- Guo L, Zhang S. Association between ideal cardiovascular health metrics and risk of cardiovascular events or mortality: A meta-analysis of prospective studies. Clin Cardiol. 2017;40(12):1339-46.

- Ogunmoroti O, Allen NB, Cushman M, Michos ED, Rundek T, Rana JS, et al. Association Between Life's Simple 7 and Noncardiovascular Disease: The Multi-Ethnic Study of Atherosclerosis. J Am Heart Assoc. 2016;5(10).

- Virani SS, Alonso A, Aparicio HJ, Benjamin EJ, Bittencourt MS, Callaway CW, et al. Heart Disease and Stroke Statistics-2021 Update: A Report From the American Heart Association. Circulation. 2021;143(8):e254-e743.

- Bundy JD, Zhu Z, Ning H, Zhong VW, Paluch AE, Wilkins JT, et al. Estimated Impact of Achieving Optimal Cardiovascular Health Among US Adults on Cardiovascular Disease Events. J Am Heart Assoc. 2021;10(7):e019681.

- Allen NB, Krefman AE, Labarthe D, Greenland P, Juonala M, Kahonen M, et al. Cardiovascular Health Trajectories From Childhood Through Middle Age and Their Association With Subclinical Atherosclerosis. JAMA Cardiol. 2020;5(5):557-66.

"The views, opinions and positions expressed within this blog are those of the author(s) alone and do not represent those of the American Heart Association. The accuracy, completeness and validity of any statements made within this article are not guaranteed. We accept no liability for any errors, omissions or representations. The copyright of this content belongs to the author and any liability with regards to infringement of intellectual property rights remains with them. The Early Career Voice blog is not intended to provide medical advice or treatment. Only your healthcare provider can provide that. The American Heart Association recommends that you consult your healthcare provider regarding your personal health matters. If you think you are having a heart attack, stroke or another emergency, please call 911 immediately."

A Long Way from Home from Achieving Health Equity in Stroke: The Stroke Council Award Lecture in 2021

Ahmad Ozair, MDThe American Heart Association (AHA) Stroke Council, one of the 16 councils within the AHA, is one of the largest councils within the organization. Amongst the awards it bestows at the major stroke-related conferences worldwide is the Stroke Council Award, a prestigious prize awarded to a single investigator at the AHA Scientific Sessions annually.1 Selection is made from amongst 'those who actively work to integrate stroke and heart disease in clinical care, education or research'.1

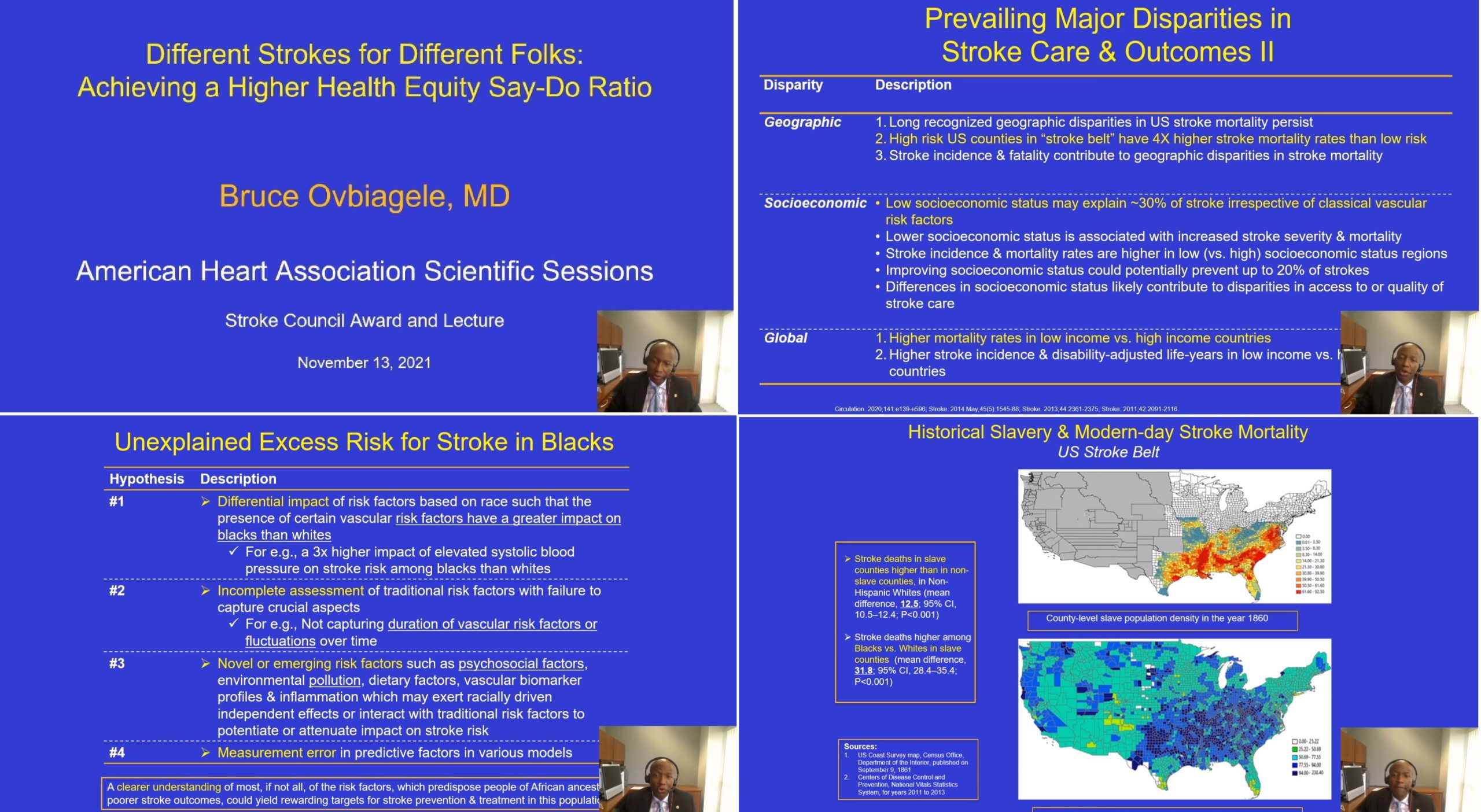

This year, the award went to Dr. Bruce Ovbiagele, MD, MSc, MAS, MBA, MLS, FAAN, FAHA, who is a Professor of Neurology and an Associate Dean at the University of California, San Francisco.2 Dr. Ovbiagele has worked on stroke care for the underserved both in the US and in Sub-Saharan Africa and has >500 publications, >100,000 citations, and an h-index of >80.3 He has previously served as a member of the NIH-NINDS Advisory Council, Chair of the International Stroke Conference, Officer of the World Federation of Neurology, and is currently a part of of the FDA Peripheral & Central Nervous System Drugs Advisory Committee.2

Dr. Ovbiagele's award lecture at the AHA (Session Number ST.AOS.380), titled 'Different Strokes for Different Folks: Achieving a Higher Health Equity Say-Do Ratio' focussed on the disparities in stroke burden and outcomes for different populations (Figure 1). Citing data from the AHA 2020 Update on Heart Disease and Stroke Statistics, Dr. Ovbiagele highlighted how African-Americans continue to have the highest stroke incidence and mortality rate of all communities, with African American men aged 45-54, for instance, having three times the mortality rate than their white counterparts.4 Dr. Ovbiagele stressed upon the widely reported and consistently poorer outcomes for women after stroke, coupled with the increased disability and lower quality of life.5 These disparities may have been further exacerbated by women having a lower likelihood of receiving thrombolysis.5,6,7

Figure 1

More than a decade ago, the AHA/ASA had put out a policy statement describing in clear terms how minority populations continue to receive suboptimal treatment for both primary and secondary stroke prevention strategies in comparison to whites.7 Health equity in stroke, however, seems to be a long way from home, with little progress reflected in the AHA 2021 Stroke Statistics Update, when put beside the AHA 2011 Update. Poorer outcomes for stroke continue to be pervasive globally, but even in high-income countries, the disparities between populations remain substantial. These disparities are evident at all levels, from stroke prevalence, first stroke incidence, stroke recurrence, to mortality.7,10

Summarizing the prevailing hypotheses (effect modification or differential impact, measurement errors, incomplete assessment, novel emerging factors) on why African Americans have an unexplained higher risk of stroke despite adjustment, Dr. Ovbiagele noted that a better comprehension of these risk factors could produce valuable opportunities for stroke prevention. Dr. Ovbiagele added a greater nuance for the audience that for different racial and/or ethnic minorities, indicators of socioeconomic status are not equivalent. In addition, they have higher exposure to multiple psychosocial stressors, which in turn have been demonstrated to increase stroke risk. For instance, Egido et al's data from INTERSTROKE demonstrated a 30% and 35% increase in stroke risk by psychosocial stress and depression, respectively.11 Dr. Ovbiagele then raised the yet unclear question of the existence of racial differences in the susceptibility and/or resilience to these psychosocial factors.

Dr. Ovbiagele laid down the various perspectives around the arguments of race being not a biological construct, but a social construct. These perspectives are well-reflected in the 2020 pledge by the board of directors of the American Medical Association (AMA) on ending racial essentialism.12 Willarda Edwards, MD, the Chair of the AMA Task Force on Health Equity, captured this elegantly as: "Recognize that when the race is described as a risk factor, it is more likely to be a proxy for influences including structural racism than a proxy for genetics".12

References:

- American Heart Association. Stroke Council Award and Lecture. Available at: https://professional.heart.org/en/partners/awards-and-lectures/lectures/stroke-council-award-and-lecture Accessed Nov 14, 2021

- American Academy of Neurology. Boards of Directors. Available at: https://www.aan.com/about-the-aan/board-of-directors-bruce-ovbiagele/ Accessed Nov 14, 2021

- Google Scholar Profile. Bruce Ovbiagele. Available at: https://scholar.google.com/citations?user=dqwMdcYAAAAJ&hl=en Accessed Nov 14, 2021

- Virani SS, Alonso A, Benjamin EJ, et al. Heart Disease and Stroke Statistics-2020 Update: A Report From the American Heart Association. Circulation. 2020;141(9):e139-e596. doi:10.1161/CIR.0000000000000757

- Bushnell C, McCullough LD, Awad IA, et al. Guidelines for the prevention of stroke in women: a statement for healthcare professionals from the American Heart Association/American Stroke Association [published correction appears in Stroke. 2014 Oct;45(10);e214] [published correction appears in Stroke.2014 May;45(5):e95]. Stroke. 2014;45(5):1545-1588. doi:10.1161/01.str.0000442009.06663.48

- Virani SS, Alonso A, Benjamin EJ, et al. Heart Disease and Stroke Statistics-2020 Update: A Report From the American Heart Association. Circulation. 2020;141(9):e139-e596. doi:10.1161/CIR.0000000000000757

- Cruz-Flores S, Rabinstein A, Biller J, et al. Racial-ethnic disparities in stroke care: the American experience: a statement for healthcare professionals from the American Heart Association/American Stroke Association. Stroke. 2011;42(7):2091-2116. doi:10.1161/STR.0b013e3182213e24

- Roger VL, Go AS, Lloyd-Jones DM, et al. Heart disease and stroke statistics–2011 update: a report from the American Heart Association [published correction appears in Circulation. 2011 Feb 15;123(6):e240] [published correction appears in Circulation. 2011 Oct 18;124(16):e426]. Circulation. 2011;123(4):e18-e209. doi:10.1161/CIR.0b013e3182009701

- Virani SS, Alonso A, Aparicio HJ, et al. Heart Disease and Stroke Statistics-2021 Update: A Report From the American Heart Association. Circulation. 2021;143(8):e254-e743. doi:10.1161/CIR.0000000000000950

- Howard VJ, Kleindorfer DO, Judd SE, et al. Disparities in stroke incidence contributing to disparities in stroke mortality. Ann Neurol. 2011;69(4):619-627. doi:10.1002/ana.22385

- AMA: Racism is a threat to public health. American Medical Association. Published Nov 16, 2020. Available at: https://www.ama-assn.org/delivering-care/health-equity/ama-racism-threat-public-health Accessed Nov 14, 2021

- Egido JA, Castillo O, Roig B, et al. Is psycho-physical stress a risk factor for stroke? A case-control study. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 2012;83(11):1104-1110. doi:10.1136/jnnp-2012-302420

"The views, opinions and positions expressed within this blog are those of the author(s) alone and do not represent those of the American Heart Association. The accuracy, completeness and validity of any statements made within this article are not guaranteed. We accept no liability for any errors, omissions or representations. The copyright of this content belongs to the author and any liability with regards to infringement of intellectual property rights remains with them. The Early Career Voice blog is not intended to provide medical advice or treatment. Only your healthcare provider can provide that. The American Heart Association recommends that you consult your healthcare provider regarding your personal health matters. If you think you are having a heart attack, stroke or another emergency, please call 911 immediately."

Highlights from #AHA21: Coffee and SGLT2 inhibitors!

Andi Shahu, MD, MHSSo much great work is being shared at the AHA. I'd like to put a spotlight on two studies that stood out from Day 2 of #AHA21!

The CRAVE Trial

The Coffee and Real-Time Assessment of Atrial and Ventricular Ectopy (CRAVE) trial attempted to address an urban myth that has been around for decades: coffee could contribute to arrhythmias. But is this actually true? The objective of this study was to assess in a more structured and scientific way to study the effects of coffee on individuals in the ambulatory setting. In this randomized crossover trial, 100 participants were each given a Fitbit Flex 2 (an accelerometer that can records step counts and number of hours of sleep), a Zio Patch (a continuously recording electrocardiogram [ECG] device), and a continuous glucose monitor to measure glucose levels. Study investigators also obtained blood samples to extract DNA to determine whether participants exhibited fast or slow caffeine metabolism genetic variants.

Participants were randomly assigned using a mobile app to either consume or avoid coffee on a day-to-day basis. Coffee consumption was validated via geo-location trackers, money incentives and daily surveys. Study investigators then compared days when people were assigned to drink coffee with those in which they were assigned to avoid it. Increased coffee consumption did not lead to an increase in atrial arrhythmias (in fact, it was associated with less supraventricular tachycardias [SVT]). However, increased coffee consumption was associated with more premature ventricular contractions (PVCs). Genetic analyses of DNA samples from participants showed that faster metabolizers were more likely to have more PVCs.

In the analysis of the Fitbit data, coffee intake was associated with 1000 additional steps on those days in which coffee was consumed, but with less sleep that same evening. Slow metabolizers of caffeine were more affected and were more likely to have reduced sleep. There were no differences in serum glucose levels with regard to coffee intake.

Study investigators concluded that coffee consumption did not lead to increased atrial arrhythmias but did increase PVCs and that coffee consumption. It also led to more physical activity, may lead to less sleep, with differential effects depending on how well people can metabolize caffeine. This is further evidence that the physiologic effects of caffeine intake are complex and varied in different populations, and should be further studied.

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=AAc0JnX90NA&ab_channel=AHAScienceNews

The EMPULSE Trial

The Empagliflozin in Patients Hospitalized for Acute Heart Failure (EMPULSE) trial was a randomized, placebo-controlled trial that assessed the safety and efficacy of the sodium glucose transporter cotransporter-2 (SGLT2) inhibitor empagliflozin in 500 patients who were hospitalized for acute decompensated heart failure (regardless of whether or not they had diabetes, HFpEF or HFrEF). This last distinction is key as many recent studies of empagliflozin have focused specifically on diabetic patients or patients with heart failure with reduced left ventricular ejection fraction (HFrEF). Primary outcomes included death, number of heart failure events (HFE), time to first heart failure event, change in baseline Kansas City Cardiomyopathy Questionnaire (KCCQ-TSS) after 90 days of treatment. Participants were randomized to empagliflozin 10 mg daily (and continued for at least 90 days) or to a placebo during their acute heart failure hospitalization.

After 90 days of treatment starting during their hospitalization for acute decompensated heart failure, participants who received empagliflozin were 36% more likely to see a clinical benefit (a composite of time to death, number of HFEs, time to HFE, and change from baseline KCCQ-TSS). There was a 35% percent reduction in death or first heart failure event. There was also greater weight loss, greater reduction in NT-proBNP and there were no safety concerns associated with taking the medication. Findings were similar in patients without and with diabetes, those with HFpEF and HFrEF as well as those with a new heart failure diagnosis or those with chronic heart failure.

In conclusion, this study showed that empagliflozin was both safe for patients to start taking during a hospitalization for acute decompensated heart failure and led to lower likelihood of death or new heart failure events – among other benefits – if the medication was started during that hospitalization, regardless of one's diabetes status or ejection fraction. More work needs to be done to better understand the mechanism by which SGLT2 improve these clinical outcomes, though some speculate that their benefits have to do with the diuretic effect of the medication. In a similar vein, EMPEROR-Preserved Trial published in the New England Journal of Medicine earlier this year showed that empagliflozin reduced the risk of cardiovascular death or hospitalization in patients with heart failure with a left ventricular ejection fraction of at least 40%, regardless of whether or not they have diabetes.

Studies such as EMPULSE and EMPEROR-Preserved provide further support for utilization of empagliflozin in all patients with heart failure – not just those with a reduced ejection fraction (for which a number of studies have already shown clinical benefit, and for which SGLT2 inhibitors are already standard of care). Lively discussions in the medical community are ongoing as to whether we should be placing all patients – with reduced and preserved ejection fraction – who are hospitalized with heart failure on an SGLT2 inhibitor, prior to discharge.

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=Vtflg2v8m8A&ab_channel=AHAScienceNews

"The views, opinions and positions expressed within this blog are those of the author(s) alone and do not represent those of the American Heart Association. The accuracy, completeness and validity of any statements made within this article are not guaranteed. We accept no liability for any errors, omissions or representations. The copyright of this content belongs to the author and any liability with regards to infringement of intellectual property rights remains with them. The Early Career Voice blog is not intended to provide medical advice or treatment. Only your healthcare provider can provide that. The American Heart Association recommends that you consult your healthcare provider regarding your personal health matters. If you think you are having a heart attack, stroke or another emergency, please call 911 immediately."

Health Equity, the Forgotten Pillar

Ayana April Sanders, PhDThis year's AHA21 Scientific Session placed an intense spotlight on understanding and achieving health equity in cardiovascular health (CVH). AHA has a broad vision for being transformative in all of the ways that structural inequities influence health outcomes. Specifically, AHA's 2024 Impact Goal states that: Every person deserves the opportunity for a full, healthy life. As champions for health equity, by 2024, the American Heart Association will advance cardiovascular health for all, including identifying and removing barriers to health care access and quality.

On Day 1 of AHA21, during the 'Cardiovascular Health After 10 Years: What Have We Learned and What is the Future?' session, we engaged with experts about the genesis of CVH, how it has been studied throughout the life span over the past decade, and methods for influencing CVH at critical life stages. Darwin Labarthe, MD, MPH, PhD, provided a historical review of the conceptual origins and definition of CVH, and the meaning of CVH in translation. CVH is defined by key features of AHA's Life's Simple 7, including assessments of diet, smoking status, physical activity, weight management, blood pressure, cholesterol, and blood glucose.

Ideal CVH is determined by the absence of clinically diagnosed CVD together with the presence of the 7 metrics. Longitudinal evidence has shown that maintaining ideal CVH is more cardioprotective than improving and achieving CVH from a lower CVH level. But US NHANES data shows that about 13% of adults meet 5 of the 7 criteria, 5% have 6 of 7, and virtually 0% have ideal CVH or meet 7 of 7 metrics. This begs the question of how do we attain and maintain a high level of CVH? Ideally, maintaining CVH by Life Simple 7 standards should be SIMPLE…just ensure that all 7 metrics are met, and you will have ideal CVH! But realistically, it is near impossible for individuals to achieve ideal CVH. It is more likely that both individual and population-level efforts are needed to achieve and maintain CVH.

From a life course perspective, high CVH in adulthood is more likely when high CVH is present in early life. But as the panelist continued to describe the state of CVH in America, we quickly learned that while high CVH is consistently associated with lower risk of cardiovascular disease (CVD), disparities in CVD rates vary by sociodemographic factors like age, sex, race/ethnicity, and educational attainment. A recent study by panelist Amanda Marma Perak, MD, MS, FAHA, FACC, and colleagues (2020) using data from the CARDIA study found that less than a third of young adult participants had high CVH, and this was lower for Blacks than Whites and those with lower than higher educational attainment. These results demonstrate that CVH is far from ideal even among younger cohorts. Over the last few decades, we have witnessed increasing rates of cardiovascular abnormalities and subclinical and overt CVD in adolescents and emerging or young adults. The low prevalence of ideal CVH in young adults suggests that factors contributing to CVD risk may be embedded at earlier life stages. The experiences that happen or do not happen in early life settings (i.e., family, households, schools, communities, etc.) are important opportunities to achieve or maintain high CVH. The drivers of health disparities, like social determinants of health (SDOH), structural racism, and rural health inequalities, are necessary to achieve sustainable health equity and well-being for all. One method is effectively developing culturally-tailored community-engaged partnerships to promote CVH. LaPrincess Brewer, MD, MPH, shared the phenomenal community-based interventions being conducted to intervene on low CVH in Black neighborhoods by addressing SDOH at the community-level. These included the Fostering African-American Improvement in Total Health CVH (FAITH!) CVH wellness program, Community Health Advocacy and Training (CHAT) program, and The Black Impact Program.

The conversation on CVH and health equity continued strong on Day 2 of AHA21 at the 'Achieving Health Equity: Advancing to Solutions' session. With a panel of leading experts in health equity research, calls for action rang out at each presentation. David Williams, PhD, argued that racial inequalities in health are fortified from centuries of established institutional/structural racism, individual discrimination, and cultural racism, which result in a significant cost to mental health and millions of African-American lives lost each year. Sonia Angell, MD, MPH built on the discussion with a call to action in investing in understudied and marginalized communities that experience poorer CVH. Importantly, as clinicians, research scholars, and policymakers, we need to consider the significant impact of spending more time addressing intervention areas with the largest impact on health, like the structural causes of health inequities. When we work to eliminate structural causes of health inequities, we can begin to spend less time and energy working on small impact areas like counseling, education, and referrals for emergency foods and housing. Ultimately, we can reduce the time and costs ofmitigating health inequities when we focus oneliminating the structural causes of health inequities.

Finally, in a powerful video,Health Equity: Patients' Perspectives, we were invited to hear the stories and experiences of those from Black and Hispanic/Latino communities who were significantly affected by health inequities and failed by their healthcare systems. The tales were jarring and left the audience and panel with a strong sense of remorse. The impact of inequalities in health has been a regular staple in marginalized communities across America for centuries. Collectively, from these voices, we recognize that patients and participants need to be treated as humans. In seeking to meet AHA's 2024 Impact Goal, I want to echo the sentiments of Kirsten Bibbins-Domingo, PhD, MD, MAS, that equity was always an important pillar in health quality and safety, but it is the forgotten pillar. We must make health equity front and center. As such, we need to 1) actively make health equity a priority and place it front and center in our professional and personal work; 2) have respect for all of humanity from all social groups; and 3) we need better science to understand how risk and disease are being experienced.

References

- Lloyd-Jones, Donald M., et al. "Defining and setting national goals for cardiovascular health promotion and disease reduction: the American Heart Association's strategic Impact Goal through 2020 and beyond."Circulation 4 (2010): 586-613.

- Enserro, Danielle M., Ramachandran S. Vasan, and Vanessa Xanthakis. "Twenty‐year trends in the American Heart Association cardiovascular health score and impact on subclinical and clinical cardiovascular disease: the Framingham Offspring Study."Journal of the American Heart Association 11 (2018): e008741.

- Benjamin, Emelia J., et al. "Heart disease and stroke statistics—2017 update: a report from the American Heart Association."circulation 10 (2017): e146-e603.

- Perak, Amanda M., et al. "Associations of late adolescent or young adult cardiovascular health with premature cardiovascular disease and mortality."Journal of the American College of Cardiology 23 (2020): 2695-2707.

- He, Jiang, et al. "Trends in Cardiovascular Risk Factors in US Adults by Race and Ethnicity and Socioeconomic Status, 1999-2018."JAMA 13 (2021): 1286-1298.

"The views, opinions and positions expressed within this blog are those of the author(s) alone and do not represent those of the American Heart Association. The accuracy, completeness and validity of any statements made within this article are not guaranteed. We accept no liability for any errors, omissions or representations. The copyright of this content belongs to the author and any liability with regards to infringement of intellectual property rights remains with them. The Early Career Voice blog is not intended to provide medical advice or treatment. Only your healthcare provider can provide that. The American Heart Association recommends that you consult your healthcare provider regarding your personal health matters. If you think you are having a heart attack, stroke or another emergency, please call 911 immediately."

Early Intervention can Lead to Prevention Of Postoperative Atrial Fibrillation after Cardiac Surgery

Devesh Rai, MDPosterior left pericardiotomy can help reduce new-onset atrial fibrillation is suggested by a late-breaking science presented by prominent researchers and cardiothoracic surgeon Dr. Gaudino at American Heart Association 2021 virtual conference on November 14, 2021.

Atrial fibrillation(AF) is the most common complication after cardiac surgery, and the incidence ranges from 15-50%.1 The incidence of postoperative AF has remained similar over the years. The researchers from the Posterior Left Pericardiotomy for the Prevention of Postoperative Atrial Fibrillation After Cardiac Surgery (PALACS) trial built upon the prior smaller studies suggesting posterior left pericardiotomy may decrease new-onset postoperative AF.2 It is an adaptive, single-center, single-blind randomized controlled trial at New York-Presbyterian Hospital.

The trial included patients undergoing coronary artery bypass grafting (CABG), aortic valve and/or aortic surgery with no history of prior AF or other arrhythmias. These patients were started on beta blockers post-procedure. The trialists screened 3601 patients and included 420 patients for randomization with posterior left pericardiotomy vs. no additional intervention. The patients were followed only during the inpatient hospitalization for primary and secondary outcomes. Interestingly, the incidence of new-onset AF was remarkably lower in the intervention group (18% vs. 32%, Relative risk (0.55), p:<0.001) compared to the no intervention group. The authors also report that the need for postoperative antiarrhythmic medications and systematic anticoagulation was considerably lower in the intervention group. However, the length of hospitalization was similar in both groups. Similarly, there was no difference in mortality.2

The decrease in the incidence of postoperative AF can be attributed to lower postoperative pericardial effusion with the posterior left pericardiotomy. This small incision created a pathway for the drainage of the pericardial fluid to the pleural area, thereby inhibiting the inflammatory pathway and atrial remodeling, which could cause AF. Prior to this, many other therapeutic interventions with antiarrhythmic medications have been studied for the potential preventive strategy of AF. Nevertheless, this is a novel surgical technique with potential for future implications.

It is noteworthy, PALACS is a single-center trial with no hard clinical outcomes and comes with limitations. Evaluating the sample size, the mean age of the population was 61 years, and 24% of the participants were women. The mean CHA2DS2VASc score for the sample was 2. An important aspect of the trial is only the inpatient follow-up of the participants; there is a small subset of patients who may develop AF even after four weeks of discharge. The design of the trial is intuitive and aims for a proof of concept regarding the surgical technique.

Dr. Subodh Verma, a prominent researcher and cardiothoracic surgeon from the University of Toronto, says, "Congratulations to the authors and investigators, this well-conducted surgical trial provides convincing proof of concept that a simple, inexpensive, generalizable, surgical adjunctive procedure of pericardial drainage can safely reduce postoperative AF after cardiac surgery" at the AHA21 while discussing the study.

References:

- Verma A, Bhatt DL, Verma S. Long-Term Outcomes of Post-Operative Atrial Fibrillation. Journal of the American College of Cardiology. 2018;71(7):749-751.

- Gaudino M, Sanna T, Ballman KV, et al. Posterior left pericardiotomy for the prevention of atrial fibrillation after cardiac surgery: an adaptive, single-centre, single-blind, randomised, controlled trial. The Lancet.

"The views, opinions and positions expressed within this blog are those of the author(s) alone and do not represent those of the American Heart Association. The accuracy, completeness and validity of any statements made within this article are not guaranteed. We accept no liability for any errors, omissions or representations. The copyright of this content belongs to the author and any liability with regards to infringement of intellectual property rights remains with them. The Early Career Voice blog is not intended to provide medical advice or treatment. Only your healthcare provider can provide that. The American Heart Association recommends that you consult your healthcare provider regarding your personal health matters. If you think you are having a heart attack, stroke or another emergency, please call 911 immediately."

Lessons from Legends in Cardiovascular Nursing

Michelle SmithA significant portion of the AHA 2021 Scientific Sessions was focused on mentorship for early career individuals in research and medicine. Insights from the Interview with Nursing Legends in Cardiovascular Science were particularly illuminating. During this session, Dr. Christopher Lee, Professor and Associate Dean for Research at the Boston College William F. Connell School of Nursing; Dr. Kathleen Dracup, Dean Emeritus and Professor Emeritus, University of California, San Francisco, School of Nursing; and Dr. Martha Hill, Dean America at Johns Hopkins University School of Nursing offered advice from their experiences mentoring individuals of varying career levels. Here are some key takeaways for individuals who want to advance their career:

Take the show on the road

Determine professional goals and how to reach them. For those interested in research, a defined program of research and possibly multiple contingency topics of study that are of interest to several funders is needed. It is also necessary to know the road, or what success looks like given the scientific focus and what one wants to accomplish during an academic career. Finally, it is important to acknowledge that there is no one pathway to success and that success is in many ways self-defined.

Do a legacy exercise

The legacy exercise, which is sometimes referred to as a eulogy or obituary exercise involves imagining your retirement party or eulogy and thinking about who you want to speak and what you want them to say about you. This reflection essentially determines what type of legacy you want to leave behind, what you want to be known for and by whom. The exercise often reveals details which are not on your CV. It might not mirror scientific goals, and possibly will not align with perceived ideas of success. Ultimately, the exercise can help one focus on the rewarding aspects of work and other parts of life, even faced with challenges.

Consider personal challenges

Mentors often observe personal challenges among both colleagues. Dr. Lee pointed out that life outside of work and issues of personal importance need to be taken into consideration. In fact, he mentioned that he sometimes advises against taking on additional work or submitting extra grants because of competing demands and priorities on other aspects of life. Dr. Lee is also adamant that the best way to have a lasting and impactful career as a scientist is to have great fulfillment in personal life.

Diversify your research team

Diversity brings great insight into fields in business and research, and in decision making. Cardiovascular nurses often do not practice alone, and it would be beneficial for research teams to reflect this. Although diversity was spoken specifically of the multi-professional nature of cardiovascular nursing research, it is not limited to it. In a general sense, investigators should seek out collaborators who share passion for research, who are concerned about the outcomes of interest, and who are more knowledgeable about the research methods. These elements can help bolster various aspects of projects.

Network

As exemplified by the speakers, connecting at conferences and in research has led to long collaborations and friendships. Whether a mentor, early career or mid careers professional, the benefits of networking can be incredibly gratifying.

Overall, the speakers addressed ways to alleviate challenges for colleagues of all career phases. Their advice diminished the pressure of preconceived ideas of success by supporting the development of personal definitions of achievement. Determining goals and paths, thinking about legacy, including diverse perspectives in projects, and expanding professional networks give individuals more power and opportunity to grow. The speakers have a wealth of knowledge, experience and advice which make them not only legends, but also champions for the success of others.

Channeling Health Care Delivery and Implementation Science in Cardiology for Improved Outcomes

Olubadewa Fatunde, MD MPHThe opening session for AHA21 was nothing sort of inspirational. In the opening session, a quote by Dr. Keith Ferdinand, Professor of Medicine and Chair of Preventative Cardiology at Tulane University, really stuck with me. The topic was how is the field of medicine adjusting in the midst of the challenges faced and inequities uncovered by the COVID pandemic? The simple answer: while positive strides have been made, there is much room for improvement. He then went on to expound about the importance of implementation science, as the best science in the world will do you no good if patients are unable to implement physical activity/dietary guidelines, understand when to take the appropriate medications, or receive preventive vaccines in time.

From the American experience with COVID, part of the difficulty in reaching the average American seems to be the emotional gap between patients and either healthcare institutions or providers. The weight evidence from the trials on COVID vaccines are clear on the efficacy and safety, particularly of the mRNA vaccines. However, delivering the messaging in a way the public will accept remains frustrating in many parts of the country. As a result, only 59% of the US population is fully vaccinated, while 68% have received at least one dose, ranking 51st in the world (1). The way we consume information is drastically different from earlier decades. In 2020, a Pew Research poll revealed more than eight-in-ten U.S. adults (86%) received news from a digital device compared to TV (68%), with those under 50 heavily skewed towards digital news consumption.(2) In this same poll, approximately 50% of adults consumed news from social media.(2, 3) In contrast, in 2015, 75% of American adults had a PCP, dropping to 64% among 30-year-olds.(4) During the last true global pandemic, that PCP was more likely to make a house call rather than see a patient 1 to 4 times a year.

The common thread for successful interventions seems to be meeting people where they are. Several panelists on the FIT session on navigating misinformation on social media, noted that as many receive news on socia media, they were motivated to explain new studies and correct misinformation on those platforms where people are likely to spend time and digest information. Admittedly, this effect is hard to measure, and many studies thus far are qualitative in nature. More concretely, two exciting trials presented at #AHA21 seem to shed some light on how we can mobilize these neural structures to improve the rates of uptake of proven behavioral & therapeutic modalities, to yield the morbidity and mortality benefits. Simply, how do we get patients to successfully take their indicated medications?

Dr. Jiang He of Tulane University presented the results of the China Rural Hypertension Control Project, an intervention in rural China utilizing nonphysician community health workers (CHW) supervised by local primary care physicians. These CHW—village doctors—were provided with basic medical training (e.g. standardized BP measurement) and tasked to deliver protocolized antihypertensive medications and counsel patients on medication adherence and lifestyle modification (5, 6). Patients were followed monthly and received discounted or free medications and home BP monitors. After 18 months, this cluster-randomized trial, yielded a 37.1% increase in achievement of goal BP control (< 130/80 mm Hg) of subjects living in intervention villages (57%) compared with those living in control villages (19.9%) (P < 0.001). The average drop in BP in the intervention group was greater by 15/7 mm Hg. (6) The use of community health workers is not a new phenomenon in developing countries. They are often trusted community members who receive training to help address community problems. The first use of CHW with no prior formal training to address problems with rural health was in China in the 1930s.(7) This model later spread to Latin America and Southeast Asia in the 1960s with varying levels of success. Certain countries—including Brazil, Bangladesh, and Kenya—have learned from these early struggles to build sustainable successful CHW models (7-9). Our colleagues in infectious disease have successfully integrated CHW to help tackle lack of adherence to Tuberculosis medications causing resistance, by CHW directly observing patients taking their medicines (DOTS).(10) In the US, CHW was recognized as a standard job classification by the US Department of Labor (US Bureau of Labor Statistics, 2010) for the first time in the 2010 census and continue to be underutilized. If the work of Dr. He and colleagues, can be translated to a form suitable to the US health system, this can hold great promise for prevention of the myriad problems stemming from uncontrolled hypertensions.

Dr. Alexander Blood, of Brigham and Women's Hospital, provides a glimpse of what this may look like. Based on prior work led by Dr. Benjamin Scirica at the same institution(11), the program uses "navigators" to communicate with patients (via phone, text, and email), pharmacists to prescribe and adjust medication as necessary, as well as an algorithm to help educate patients, integrate data, and coordinate care. (12, 13) As a result, systolic blood pressure was reduced by 10 mm Hg and LDL cholesterol by 45 mg/dL in approximately 10,000 participants enrolled. In an interview with TCTMD, Dr. Blood compared this program to Warfarin management, where the physician writes the initial prescription and the Pharmacy and Warfarin clinic maintain patient's INR on a weekly basis. It is unlikely that quarterly or biannual visits will yield effective control in patients with poor health literacy. For patients that needed higher intensity care, they were referred to their physician (12, 13). An important aspect of this trial is the results were consistent in populations typically underserved by the medical system–Blacks, Hispanics, and non-English speaking populations. Dr. Blood noted, "…if you structure the way you're reaching out to patients, engaging them, and communicating with them—if you're intentional and equitable in the way you make that type of outreach—it's possible to engage, enroll, and help patients reach maintenance at similar rates across these subpopulations that are traditionally underserved in medicine." (12)

In summary, while amazing new discoveries & technologies continue to reshape what is possible in cardiology, it is equally important to apply the same ingenuity to scaling up what we already know works and meet people where they are, in order to guide them to best health that science can offer.

References:

- Hannah Ritchie EM, Lucas Rodés-Guirao, Cameron Appel, Charlie Giattino, Esteban Ortiz-Ospina, Joe Hasell, Bobbie Macdonald, Diana Beltekian and Max Roser (2020) – "Coronavirus Pandemic (COVID-19)". Published online at OurWorldInData.org. Retrieved from: 'https://ourworldindata.org/coronavirus' [Online Resource]. [Available from: https://ourworldindata.org/covid-vaccinations?country=USA.

- Shearer E. More than eight-in-ten Americans get news from digital devices2021. Available from: https://www.pewresearch.org/fact-tank/2021/01/12/more-than-eight-in-ten-americans-get-news-from-digital-devices/.

- Shearer E, Mitchell A. News Use Across Social Media Platforms in 20202021. Available from: https://www.pewresearch.org/journalism/2021/01/12/news-use-across-social-media-platforms-in-2020/.

- Levine DM, Linder JA, Landon BE. Characteristics of Americans With Primary Care and Changes Over Time, 2002-2015. JAMA Intern Med. 2020;180(3):463-6.

- Sun Y, Li Z, Guo X, Zhou Y, Ouyang N, Xing L, et al. Rationale and Design of a Cluster Randomized Trial of a Village Doctor-Led Intervention on Hypertension Control in China. Am J Hypertens. 2021;34(8):831-9.

- Neale T. Village-Level Intervention Nets Big BP Control Gains in Rural China. TCTMD. 2021. https://www.tctmd.com/news/village-level-intervention-nets-big-bp-control-gains-rural-china [Accessed November 14, 2021]

- Perry H. A Brief History of Community Health Worker Programs. https://www.mchip.net/: USAID; 2013. p. 14.

- Lehmann U, Sanders D. Community health workers: What do we know about them? The state of the evidence on programmes, activities, costs and impact on health outcomes of using community health workers. School of Public Health, University of the Western Cape, Evidence and Information for Policy DoHRfH; 2007.

- Rosenthal EL, Wiggins N, Ingram M, Mayfield-Johnson S, De Zapien JG. Community health workers then and now: an overview of national studies aimed at defining the field. J Ambul Care Manage. 2011;34(3):247-59.

- Farmer P, Kim JY. Community based approaches to the control of multidrug resistant tuberculosis: introducing "DOTS-plus". BMJ. 1998;317(7159):671-4.

- Scirica BM, Cannon CP, Fisher NDL, Gaziano TA, Zelle D, Chaney K, et al. Digital Care Transformation: Interim Report From the First 5000 Patients Enrolled in a Remote Algorithm-Based Cardiovascular Risk Management Program to Improve Lipid and Hypertension Control. Circulation. 2021;143(5):507-9.

- O'Riordan M. Pharmacist-Led Intervention Slashes LDL and BP in 10,000 Patients. TCTMD. 2021. https://www.tctmd.com/news/pharmacist-led-intervention-slashes-ldl-and-bp-10000-patients?utm_source=TCTMD&utm_medium=email&utm_campaign=Newsletter111321 [Accessed November 14, 2021]

- Blood AJ CC, Gordon WJ, et al. Digital care transformation: report from the first 10,000 patients enrolled in a remote algorithm-based cardiovascular risk management program to improve lipid and hypertension control. Presented at: AHA 2021. November 13, 2021.

Adding to Statins: Achieving Optimum Reduction of "Bad" Cholesterol

Khairunnisa Semesta, MAAtherosclerotic cardiovascular disease (ASCVD) is the number one cause of death in the Western world.[1] Since 2016, cardiovascular diseases have caused 1 in 3 deaths in the United States, and this trend is expected to continue in the future. There is a well-established relationship between ASCVD and elevated levels of low-density lipoprotein C (LDL-C), often called "bad" cholesterol because of its potential to accumulate in the blood vessels and contribute to the formation of fat plaques.[2] People with familial hypercholesterolemia (an autosomal dominant genetic disease caused by mutations in the LDLR, LDLRAP, APOB, and PCSK9 genes)[3] are also at risk for ASCVD due to their genetic predisposition to high cholesterol levels.

Currently, the standard of care is statin, a group of drugs that inhibits the HMGR enzyme, a key player in the cholesterol synthesis pathway. Over 55% patients undergo statin management to lower their LDL-C levels and consequently reduce morbidity and mortality.[4] However, 7 out of 10 patients on statins do not achieve their LDL-C goal. In addition, patients on statins still have residual risk of experiencing cardiovascular events and premature mortality.[5] This is due to multiple factors: nonadherence to statin management, which typically is consumed daily; drug intolerance due to the development of statin-associated muscle symptoms[6]; heterogeneity in response[7]; and others. As such, patients who are unable to control their cholesterol levels on maximum statin dose typically require an additional therapy.

Exploring additional therapies for patients who are unable to control their cholesterol levels on statins alone is the goal of the Add on Efficacy: Oral, Nonstatin Therapies for Lowering LDL-C Program in Scientific Sessions 2021, presented by Harold Bays, MD (Medical Director and President of the Louisville Metabolic and Atherosclerosis Research Center) and sponsored by Esperion Therapeutics. Until 2020, there was only one FDA-approved oral nonstatin therapy for ASCVD management: a drug called ezetimibe, which inhibits intestinal cholesterol absorption.[8] In 2020, bempedoic acid (Nexletol™) and bempedoic acid plus ezetimibe (Nexlizet™) were approved as adjuncts to diet and maximally tolerated statin therapy for patients with ASCVD or familial hypercholesterolemia who require additional lowering of LDL-C. Bempedoic acid inhibits ACL, a key enzyme in the cholesterol synthesis pathway. By week 12 of treatment, bempedoic acid and the combination of bempedoic acid and ezetimibe led to 17-18% and 38% and mean reduction of LDL-C, respectively, compared to patients given placebo and maximally tolerated statin dose.

Although statins have typically been the first line therapy for the management of ASCVD, current trends point to the need of developing additional and orthogonal therapies to achieve optimal LDL-C levels. To this end, multiple therapies are used clinically, including oral medications like bempedoic acid, ezetimibe, and bile acid sequestrants as well as other forms of therapeutics like PCSK9-inhibiting antibodies.[9] Beyond this session on non-statin therapies, Scientific Sessions 2021 provides other updates on current clinical management and emerging breakthroughs in cardiovascular health – make sure you tune in to other sessions on November 14-15, 2021!

Reference

[1] Nichols M, et al. (2014) Eur Heart J 35:2950–9

[2] Mihaylova, B. et al. (2012) Lancet 380:581–90

[3] Bouhairie, V. E. and Goldberg, A. C. (2015) Cardiol Clin 33.2: 169-79

[4] Bittner, V. et al, (2015) Journal of the American College of Cardiology, 66.17: 1873-1875

[5] Go, A. S., et al. (2014) Circulation 129: e28-e292

[6] Ward, N. C., et al. (2019) Circ Res 124:328–350

[7] Akyea, R. K. et al. (2019) Heart 105:975–981

[8] Miura, S. and Saku, K. (2008) Intern Med 47.13: 1165-1170

[9] Gupta, M. et al. (2020) Expert Opin investing Drugs 29(6):611-622.

"The views, opinions and positions expressed within this blog are those of the author(s) alone and do not represent those of the American Heart Association. The accuracy, completeness and validity of any statements made within this article are not guaranteed. We accept no liability for any errors, omissions or representations. The copyright of this content belongs to the author and any liability with regards to infringement of intellectual property rights remains with them. The Early Career Voice blog is not intended to provide medical advice or treatment. Only your healthcare provider can provide that. The American Heart Association recommends that you consult your healthcare provider regarding your personal health matters. If you think you are having a heart attack, stroke or another emergency, please call 911 immediately."

How To Blog About Industry When You're Changing Careers

Source: https://earlycareervoice.professional.heart.org/blog/

Posted by: monsourguideare.blogspot.com

0 Response to "How To Blog About Industry When You're Changing Careers"

Post a Comment